An Overview Of Our Solution

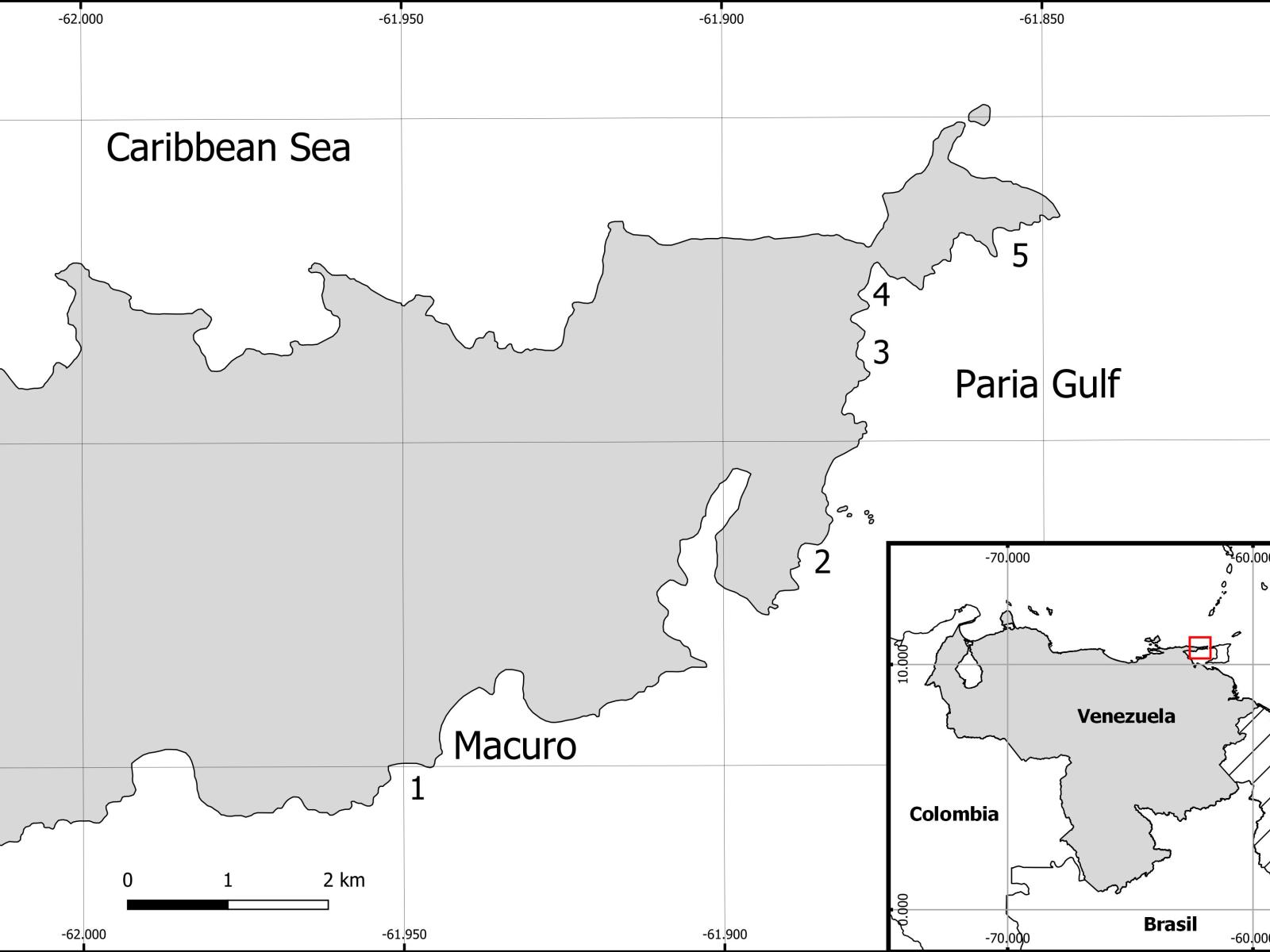

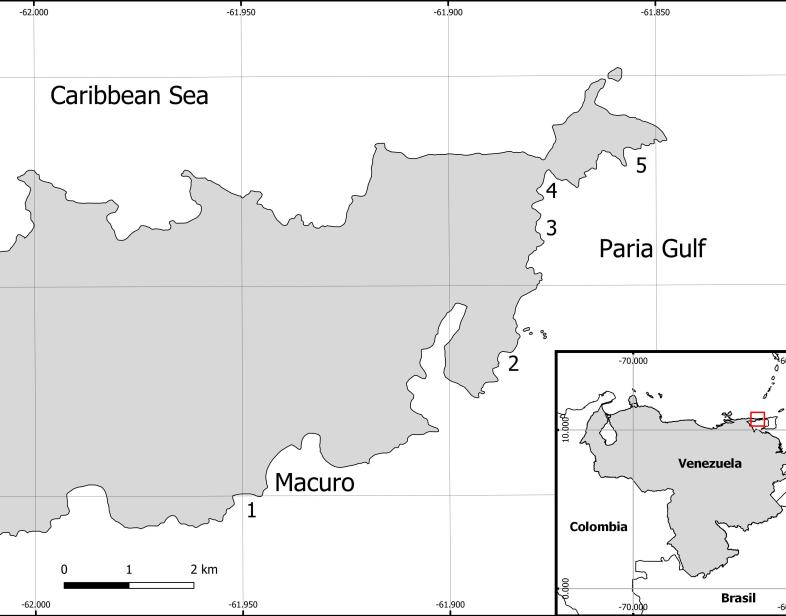

Near the estuary of the Orinoco River Delta (Venezuela), and the Peninsula de Paria National Park Mountains we can find several small beaches where vulnerable leatherback and the critically endangered hawksbills sea turtles laid their nests between the late dry and the top of the rainy season of each year. The region in the early XXI century and before had a strong poached pressure coming from the neighbor fishermen town of Macuro. Through weekly onboat patrolling, setting the example with the fishermen of the reasons why not to consume turtles, and environmental education, our conservation project reduced nests poaching from 88% (in the year 2003 when the Environment Ministry started the project) to 5% (season 2022). We aim to continue our conservation work with the beach patrolling, nests management and education of the local community of Macuro

- Population Impacted: 1,500

- Continent: South America

First name

Last name

Organization type

Email Address

Context Analysis

We are working in the Gulf of Paria, a very remote place of the northeastern Venezuela, where no roads are available due to the stepped mountains. Then, boat transportation or long walks are mandatory. Macuro is a fishermen town with long tradition of sea turtle consumption until the end of XX century. In the year 2001, the Venezuelan Environment Ministry (Minec) attended an illegal trade denounce, regarding selling of turtle products in the southern city of Guiria. A first team from Caracas reached the port city, founding nothing. However, we traveled by boat until Macuro, where people said came the illegal products. Just finding there: poached nests and turtle carcass by dozens.

The next years (2003-2012) Minec approved a proper budget to gather the basic data and logistic: exact number of poaching, amount of fishermen's boats, sea turtle species and seasonality, fishermen attitudes through surveys, start the training of possible local assistants, and try to reduce the illegal trade with regular patrolling, setting the example, and environmental education.

Our overview of the results are: that the region is a very pristine National Park, with good fishing, cacao, and coffee products potential. The surrounded estuarine sea has several small beaches where hawksbill sea turtles had the main continental rookeries of Venezuela, but with high risk to be poached. Nevertheless, the human community is very poor due to remoteness, lack of services (long period with no electricity and telecommunications), bad education of the adults, no processing industries, and tribe with Malaria illness which affect mainly the children.

In conclusion, is an extraordinary place to preserve nature and sea turtles with the cooperation and acceptance of local assistants, park rangers, seamen, teachers and collaborators.

Describe the technical solution you wanted the target audience to adopt

We first implemented a training of a local force of sea turtle assistants with people between 18 and 65 years old of the Macuro town in 2005. After the training of 70 persons, we selected 15 to start work in the next year. In 2009 we reduced the local assistant force into 8, the better personal amount needs it to attend sea turtle patrolling, nests census and rescue, nursery maintenance, environmental education, and beach cleanings.

After the cease of governmental funding, we create alliances with Venezuelan private donors in 2014 until 2019. However, since 2020 we begun to be funded by USA foundations trough NGOs, these donations reboot patrolling, and especially environmental education of the primary and secondary local schools. Our local assistant earns more than the rural minimum wage, stimulating the nature conservation job.

Describe your behavioral intervention.

First of all, we tell the people of the Paria Gulf that nature and wildlife must be protected. Second, we explain that is also forbidden by national and international laws, the consumption and trade especially of sea turtles. Moreover, for hawksbill shell, eggs and meat. In third place, we set the example working with the local team doing patrols, rescuing nests and avoid poaching. Several fishermen and persons, do not share this vision, but these suspects represent the furtive hunters with an estimate of 15 inhabitants whom produce around 7% of nests poaching each year in average (Balladares et al 2014, Balladares et al 2020).

Contracting and training local assistants is a way to find allies. Besides, we have an informal control of the boaters and national guard informers. But the environmental education to the youngers at schools, and in occasions to adults, is a way to change the minds and behaviors. Beach and town cleanings are performed through the park rangers, teachers and our assistants and collaborators.

Results, apart from the poaching reduction in two decades, is the fishermen reports on more juveniles observed in open waters. Changes of attitudes, first on the female population, and second in the children or teenagers. When you ask the youngers what they want to be, the answer changed from military or tugs, into park rangers, biologists, medics.

Behavioral Levers Utilized

As needed, please explain how you utilized the lever(s) in more detail.

Emotional appeal: We tell all the Macuro inhabitants that sea turtles especially hawksbill are very abundant in the region, but comsumption could diminish the regional population, and this reptiles are key especies to increase fisheries and benthic resources like coral reef. In that sense, feel pride and responsability for his natural resources.

Information: We give ocasional chats to fishermen, weekly environmental education to the primary and secondary school, all about the basic concepts of ecology, national parks, and impacts over the nature.

Rules and Regulations: We also explain to the comunity that sea turtles and the National park are resources protected by law. So, they will be punished if they damaged or trade with these.

Social influences: We set our conservation projects as the proper way to deal with nature. Do not harm or trade with the natural resources protected by laws, especially the sea turtles. We promote our field assitants and park rangers as the local heroes.

Describe your implementation

The specific activities are weekly boat patrolling during the nesting season in the five main beaches close to Macuro town with rented local boaters, and four assistants. The reproductive season is couple with Environmental education at the primary and secondary Macuro schools, this is between March and October each year. And additional nature protection is backup with the help of 6 park rangers patrolling the mountains of the Paria NP the whole year twice a week detecting illegal activities and reporting biodiversity observation using SMART software.

The boat patrolling, control sea turtle poaching as an early warning and prevention at the nesting beaches. Our work with the patrolling boat and the field assistants is an example of the proper way of conduct with these reptiles. Regarding the environmental education of the scholar’s population, we evaluate assistants as an extra academic activity for increased number of students who wants to improve himself. Sometimes including fathers and representants of each pupil with visits to the sea turtle nursery at the town, cleanings and presentations. Park rangers are part of the example of the proper conduct with nature.

We enable conditions for the nature protection through training of local technicians as seaman assistants and park rangers with SMART, and designing an environmental education program adapted by two local teachers. Meanwhile, offering a compensation and motivational extra salary.

Our key success is the reduction in nests poached by year, increased amounts of environmental educated students and locals, plus the numbers of illegal activities detected monthly by the park rangers.

The main obstacle is the remoteness of Macuro, lack of electricity, fuel scarcity, communications and fundings. We overcome with alliance between regional and national institutions for the transportation and fuel facilities. Finally, we gave cellular phones to our local team to improve comunications.

Describe the leadership for your solution. Who is leading the implementation?

I am the coordinator of the Sea Turtle Conservation Project in the Gulf of Paria since the year 2005. I am use to travel from Caracas where I live and work to Macuro between one and 8 times a year. Myself with the help of a retired environmental journalist established the first alliance with the local people, boaters, field assistants’ formation, teachers, fishermen, and the basic logistic to make possible the program.

The inhabitants of Macuro are Afro-Caribbean people who speak Spanish, but is possible to find old persons that could speak Patois, and some youngers speaking English. The senior ones have a strong tradition of sea turtle consumption, but after 20 years of law enforcement trough setting the example, change of behaviors, and education; the new generations learn another way to deal with nature.

Share some of the key partners or stakeholders engaged in your solution development and implementation.

Basically, our projects in the Gulf of Paria connect in a polite manner the Venezuelan Environment Ministry (Minec) and the National Park Authority (Inparques) with the real problems of furtive illegal hunting, and the solutions with the main focal town in the region, Macuro, and his inhabitants.

The first decade (2003-2012) saw the start of the conservation project completely cover by the State. It was a success, not only reducing poaching, giving new jobs, and educating the inhabitants. The positive conservation results for the sea turtles were remarkable, reduction of nests poached, and hatchlings liberated. Moreover, the chance of attitudes of the locals in a general view regarding his natural resources.

However, the second decade (2013-2022) suffered at the beginning of the socio-economic crisis of Venezuela. The state diminished at minimum the funds, so patrolling had several deficiencies, environmental education was abandoned, and as result nest poaching rise at 13% in 2017, the next years 2019-2020 showed a very low numbers of hatchlings released (less than 2500). We searched for national private donors, and in 2021 reach an alliance with foundations in the USA (Global Conservation, SEE Turtles NGO, and MCAF-NEaq) which reboots funds, technology, and the way we handle the natural resources plus retake of the Environmental Education in 2022.

In the mean time, we keep the governamental permits, stablished alliances with Venezuelan NGOs like Provita serving as treasury and administration of international funds. Moreover we also have alliances with FUDENA (the oldest environmetal NGO of Vnzla) and in 2017 started to study our data under the academic vision of the Universidad Central in Caracas processing all the nestings numbers under the scope of the Ecology of Poppulations.

Who adopted the desired behavior(s) and to what degree? Include an explanation of how you measured a change in behavior.

Taking into account a human local population of 1500 inhabitants, we estimate that before we started the project, 300 persons were directly involved on the illegal consumption and trade of sea turtles’ products. Our precise numbers are only related with the nest numbers (Balladares et al, published papers since 2014 until 2022).

Based on early informal interviews around the year 2005. Macuro have around 80 fishing small boats which sustain around 400 fishermen families. Moreover, occasional smallest village approach Macuro beaches looking for fishing grounds and sea turtles, approximately 50 more anglers. Of this, 30% declare that they consume and trade sea turtles. Another informal poll between the inhabitants founds close to 150 persons that look for these reptiles.

In the last five years, people from Macuro improved his attitude regarding nature preservation including the anglers. In a quick poll in 2021, only 10% of the inhabitants, tell you that they still look for sea turtles.

How did you impact the environment (biodiversity conservation, ecosystems, etc.)? Please be specific and include measurement methodology where relevant.

We have a yearly record of each season and more detailed since 2009 when standardization data is taken on five main beaches, plus three more sites including the beach of Macuro town. Since then, the average is 124.71 ± 9.63 hawksbill nests/year, regarding poaching of nests we reduced the illegal activity by humans in 5% in 2022 (7 nests) thanks to the early patrolling of the beaches. Last year was 7.48% (11 nests) from a total of 147 nests, all hawksbills, and this include two nests predated by foxes. Total amount of hawksbill hatchlings liberated were 9.226, which was 24% more than year 2021 (6511) -average 6.276 ± 711 h/year since season 2006. All data results of boat patrolling.

Regarding environmental education our recent numbers of educated youngers are 100 students in 2022, 60 of the Primary school and 40 of the Secondary school, of a total of 300 pupils in Macuro. We aim to reach 150 students this year 2023 and retake two chats with the fishermen and women of the community

How has your solution impacted equity challenges (including race, ethnicity, social class/income, indigenous communities, or others)?

We contracted local assistants only, people from Macuro, like the park rangers and teachers. When we conduct trainings and chats, we focus on the persons more honest, capable and with economic needs. We also try to include people with particular disabilities, meanwhile they can understand the work and his efficiency. We also try to contract women, and we have positive experience with two of them as park rangers.

As we mention above, we trained 70 persons at the start of the program, including all ages, race, incomes. We selected the best 15 as the first assistants. In the first decade maintain 8. With the diminishing funds and problems in 2014 we only keep two. In the last year 2022 we grow again as 4 field assistants, 6 park rangers, two teachers and two boaters. The majority are Afro-Caribbeans and persons in need of a good job.

What were some social and/or community co-benefits?

Besides from honest, better paid and technical job, we pay extra bonus for extra works. We update work materials and infraestructure when is possible and funds are available from donors national and international. When a construction is need it, we look for workers in Macuro, allowance and meals are purchased locally specially fish and vegetables. We are planning for the next two years to build a Park rangers base and beach camp watch.

What were some sustainable development co-benefits?

The training of teachers as enviromental educators is the recent achievement of our projects in Macuro. They adapt the program of the year and teach to the diferent levels of education.

The park rangers were reactivated and equiped in 2021 with the funds of Global Conservation, especially two women contracted highlight the work in the National Park area.

Finally, we have a sand nursery for sea turtle nests in Macuro, the same is maintained and updated each season with the help of foundations.

Sustainability: Describe the economic sustainability of your solution.

As we mention before, the Venezuelan State trough Environment Ministry (Minec) pay the whole project the first decade. However, since 2020 we depend on international fundings. Several national private donors are still helping, but we convince Minec, and the National Park Authority (Inparques) to improve fundings, especially in kind when budgets as possible.

Since 2021 we are been funding by MCAF, and Global Conservation until 2025.

Another source of funding is evaluating tourism respecting the capacity of charge of the Paria NP, and specially the tiny and sensitive nesting beaches. We are planning this formula in a respectful manner not only with the environment, beside the local economy and the benefits to the conservation programs.

Return on investment: How much did it cost to implement these activities? How do your results above compare to this investment?

Including, the Global Park Defense system and the Sea Turtle Conservation projects in Macuro, we invest 32000 USD a year for around 6 park rangers, 4 seaman assistants, 2 teachers, one boater, one coordinator, and one liason officer. Only considering hatchling release, which is the product of avoiding poaching and carefully nursery of the eggs. We released in the season 2022 a maximum of 9226 hawksbill hatchlings, and received from SEE Turtles NGO and MCAF a total of 16000USD. Then, each hatchlings cost 0.57 USD; other places need more than two USD.

The environmental educational program invested 2700 USD last year, which benefit two local teachers, one coordinator and 100 students. So, teach each pupils cost 27USD in 2022.

How could we successfully replicate this solution in Latin America?

Sea turtle projects around the world particularly on underdeveloped countries work with local communities and try to convince inhabitants not to poach and instead collaborate with the conservation strategies. One of the main examples is Costa Rica, on the very long beach of Tortuguero National Park (22 miles beach extension). The Sea Turtle Conservancy STC started to hire local people of the Tortuguero town to patrol on foot since the 1970s, then constructed a visitor center in 1985 which serve for education and tourism.

Our reality in Venezuela with Macuro is different, we work in an impossible place to use cars and walk eficiently, we have to use boats. But our species is one of the most critically endangered species of sea turtles, and this small population need to be protected. Only to work one reproductive season in the Paria Gulf we budget 17000 USD a year for a team of ten persons which cover boat rent, nursery maintaining, motivational salaries, field trips, and extras.