An Overview Of Our Solution

- Population Impacted:

- Continent: Africa

Organization type

Population impacted

Size of agricultural area

Production quantity

People employed

Describe your solution

Describe your implementation

External connections

What is the environmental or ecological challenge you are targeting with your solution?

Describe the context in which you are operating

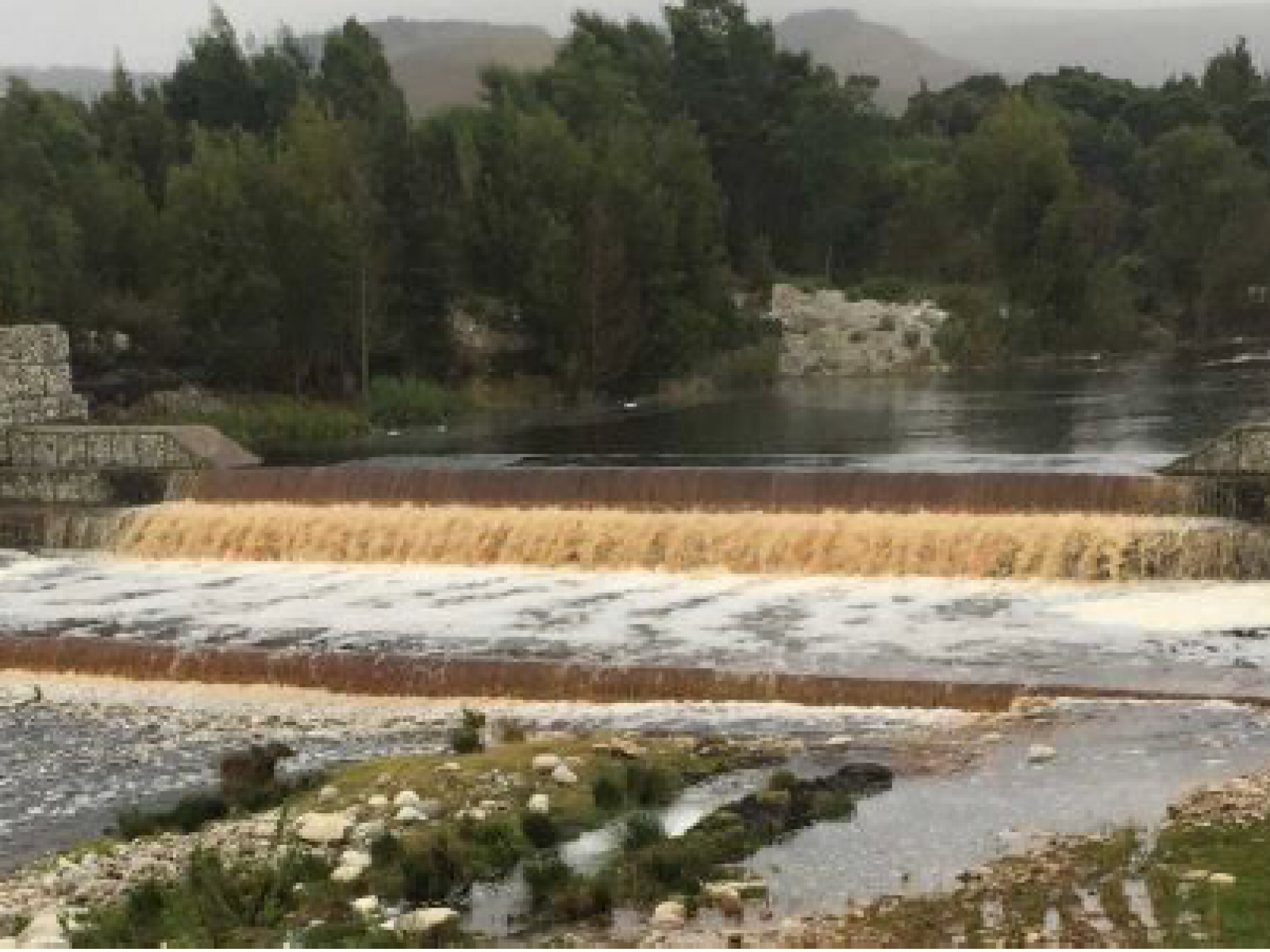

The Duiwenhoks River supports much of the municipal area (population of 52,000). Around 13,000 individuals are involved in the agriculture sector, about a quarter of the population, either as farmers or farmworkers. Much of the population is considered to be historically disadvantaged. 45% of the population has some primary school education, and only 33% some secondary school education. So the role of agriculture is vital – environmentally, economically and socially. If the river is irreparably damaged, a lifeline of the community is lost.

But the river’s role stretches beyond agriculture. It’s the main source of water for 4 towns: Heidelberg, Puntjie, Vermaaklikheid, Slangrivier. Heidelberg is the largest, with a population of 8000. Aside from a bentonite mine (employing about 50 people), most people here work in agriculture. The water scheme, Overberg Water, draws its water from the Duiwenhoks, providing water to 600 households and farming operations.

How did you impact natural resource use and greenhouse gas emissions?

Language(s)

Social/Community

Water

Food Security/Nutrition

Economic/Sustainable Development

Climate

Sustainability

The Duiwenhoks Flood Works was initially funded by local government, following the floods of 2004. These Disaster Funds allowed R40-million to be spent on the construction of the groyne and weir structures. However, these funds have leveraged funds from numerous other sources, including private landowners, who today co-fund invasive alien clearing work in the area, as well as funding from the National Department of Environmental Affairs (also for invasive alien clearing). While few landowners could afford the construction work that has taken place to stabilise the river, it has led to new landowner support to encourage a healthier river system, as well as support from other conservation agencies such as CapeNature.

Return on investment

Entrant Banner Image